Brand new science shows how hearing loss can affect your brain – which can create problems in your life.

Many people think hearing issues are just a small annoyance. A missed word here or there, or a few complaints about the TV being too loud.

But the latest science shows just how critical hearing is to your brain. Good hearing helps your brain to:

1. Keep listening effort low

2. Reduce the load on your brain

3. Avoid reorganized brain functionality

4. Avoid accelerated cognitive decline

5. Avoid accelerated brain volume shrinkagei

And that’s not all: When bad hearing affects the brain through lack of treatment or inadequate treatment, it can lead to serious problems in life.

On the other hand, good hearing – with well treated hearing loss – may help to:

1. Avoid social isolation and depression

2. Avoid poor balance and fall-related injuries

3. Avoid Alzheimer’s and dementiaii

While that may sound daunting, the good news is that we hearing experts are looking into the brain science of hearing more and more.

Amazing new insights into how hearing works in the brain

Hearing is actually thinking.

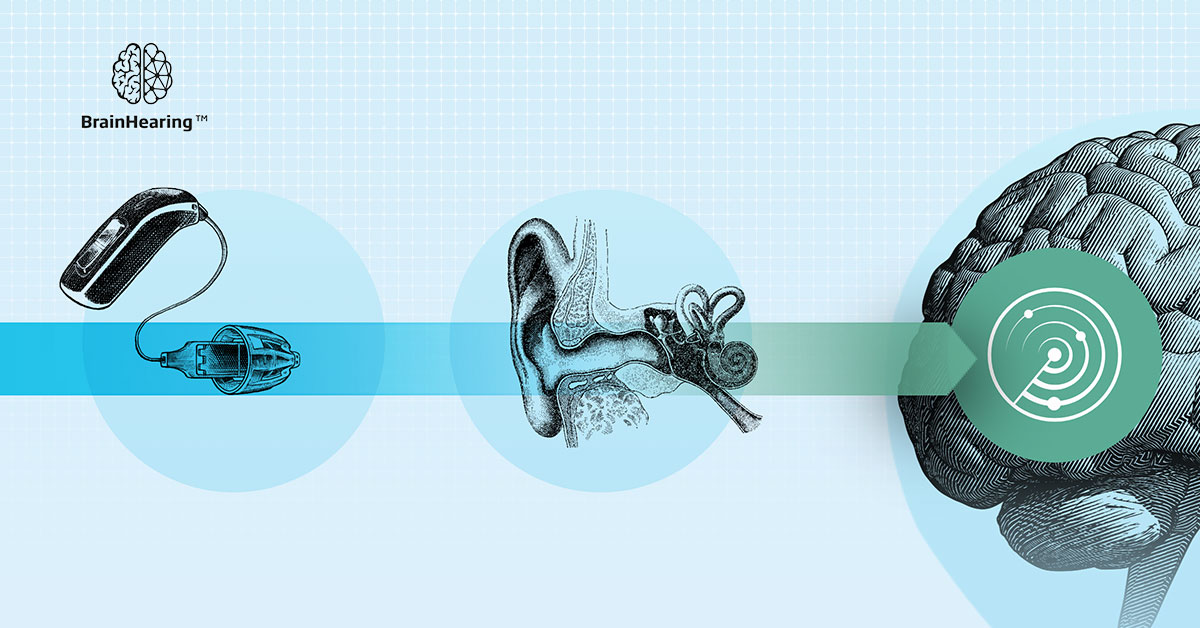

The ears gather sound, but it’s the brain that makes sense of it. So perhaps it’s less surprising that bad hearing affects the brain when we look at it this way.

How hearing works in the brain

When sounds come to the ear, they are converted into a ‘neural code’ of information. This is what the brain needs to use, so the quality of this neural code is critical.

The brain expects and needs the neural code to contain information about all of the sound around you (the full sound scene).

Because we have discovered this, we are now better able to make hearing aids with the brain’s needs in mind – ones that deliver the full sound scene, and high-quality neural code.

Why it’s so important your hearing aids are brain-friendly

These ‘brain-friendly’ hearing aids are proven to make it easier for the brain and can help to avoid all of the possible negative consequences mentioned above.

But how does hearing loss lead to such dramatic things as dementia and poor balance?

Well, hearing is a vital and fundamental sense. Like vision, it enables us to do many other things more easily.

If it isn’t working as it should, it makes other things more difficult because your brain will lack the information it needs.

This can start a spiral of effects.

First, conversations are a bit harder to follow and can be confusing. The brain has to work harder, which leaves less mental capacity for other things like remembering what is said.iii

Consequently, people may become more tired or stressed by socializing. They can become socially isolated and prefer to stay at home or avoid social situations.iv

This means less stimulation for the brain’s hearing centre, which can lead the visual centre and other senses to compensate – changing the functionality of the brain.v

If the brain has to work against the natural way it processes sound, it can even lead to accelerated shrinkage of the brain’s volume.vi

The increased mental load combined with the lack of stimulation and reorganized brain functionality is linked to accelerated cognitive decline.vii

The result is that the risk for dementia is increased five-fold for severe-to-profound hearing loss, three-fold for moderate hearing loss and two-fold for mild hearing loss.viii

Good hearing health is good brain health

Those are the possible consequences of untreated or poorly treated hearing loss.

However, they needn’t happen at all. And to reduce these risks, you need to take good care of your hearing.

Read our 3 tips on what you can do to keep your brain healthy

We recommend that you get professional hearing advice. An audiologist can give you a hearing test, and if you need hearing aids, they can advise you on good, brain-friendly hearing aids and set them up so they support your brain.

Find an audiologist near me

-----------------------------------

i 1. Pichora-Fuller, M. K., Kramer, S. E., Eckert, M. A., Edwards, B., Hornsby, B. W., Humes, L. E., ... & Naylor, G. (2016). Hearing impairment and cognitive energy: The framework

for understanding effortful listening (FUEL). Ear and Hearing, 37, 5S-27S. 2. (Rönnberg, J., Lunner, T., Zekveld, A., Sörqvist, P., Danielsson, H., Lyxell, B., ... & Rudner, M. (2013).

The Ease of Language Understanding (ELU) model: theoretical, empirical, and clinical advances. Frontiers in systems neuroscience, 7, 31.) 3. Sharma, A., & Glick, H. (2016).

Cross-modal re-organization in clinical populations with hearing loss. Brain sciences, 6(1), 4. 4. 1. Lin FR, Ferrucci L, An Y, et al. Association of hearing impairment with brain volume changes in older adults. NeuroImage. 2014;90:84-92. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.12.059. Age-related hearing loss and cognitive decline—The potential mechanisms linking the two. Auris Nasus Larynx, 46(1), 1-9. 5. Lin FR, Ferrucci L, An Y, Goh JO, Doshi J, Metter EJ, et al. Association of hearing impairment with brain volume changes in older adults. Neuroimage 2014;90:84–92.

ii 1. Amieva, H., Ouvrard, C., Meillon, C., Rullier, L., & Dartigues, J. F. (2018). Death, depression, disability, and dementia associated with self-reported hearing problems: a 25-year

study. The Journals of Gerontology: Series A, 73(10), 1383-1389. 2. Lin, F. R., & Ferrucci, L. (2012). Hearing loss and falls among older adults in the United States. Archives of

internal medicine, 172(4), 369-371. 3. Lin, F. R., Metter, E. J., O’Brien, R. J., Resnick, S. M., Zonderman, A. B., & Ferrucci, L. (2011). Hearing loss and incident dementia. Archives of

neurology, 68(2), 214-220. 4. 1. Livingston G, Sommerlad A, Orgeta V, et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care. The Lancet. 2017;390(10113):2673-2734. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31363-6

iii (Rönnberg, J., Lunner, T., Zekveld, A., Sörqvist, P., Danielsson, H., Lyxell, B., ... & Rudner, M. (2013). The Ease of Language Understanding (ELU) model: theoretical, empirical, and clinical advances. Frontiers in systems neuroscience, 7, 31.)

iv Amieva, H., Ouvrard, C., Meillon, C., Rullier, L., & Dartigues, J. F. (2018). Death, depression, disability, and dementia associated with self-reported hearing problems: a 25-year

study. The Journals of Gerontology: Series A, 73(10), 1383-1389.

v Sharma, A., & Glick, H. (2016). Cross-modal re-organization in clinical populations with hearing loss. Brain sciences, 6(1), 4.

vi Lin FR, Ferrucci L, An Y, Goh JO, Doshi J, Metter EJ, et al. Association of hearing impairment with brain volume changes in older adults. Neuroimage 2014;90:84–92.

vii Uchida, Y., Sugiura, S., Nishita, Y., Saji, N., Sone, M., & Ueda, H. (2019). Age-related hearing loss and cognitive decline—The potential mechanisms linking the two. Auris Nasus Larynx, 46(1), 1-9.

viii Lin, F. R., Metter, E. J., O’Brien, R. J., Resnick, S. M., Zonderman, A. B., & Ferrucci, L. (2011). Hearing loss and incident dementia. Archives of neurology, 68(2), 214-220.